How I Finally Learned to Display Figures by Color (And Why Your Data Viz Probably Looks Like a Rainbow Threw Up)

Contents

- How I Finally Learned to Display Figures by Color (And Why Your Data Viz Probably Looks Like a Rainbow Threw Up)

- Your Data Type Dictates Everything (Seriously, Stop Guessing)

- Categorical Palettes: When Your Data Categories Are Apples, Oranges, and Awkward Silences

- Sequential Palettes: Because Numbers Actually Have an Order (Who Knew?)

- Diverging Palettes: When Zero Actually Means Something Important

Displaying figures by color or theme in data visualization saved my last quarterly presentation from complete disaster, and I’m about to show you exactly how to avoid the mistakes that almost tanked mine.

Look, we’ve all been there.

You spend hours crafting the perfect chart, plug in your data, and then realize your color choices make it look like a kindergarten art project gone wrong.

Your boss squints at the screen, your colleagues exchange confused glances, and nobody can tell which line represents actual revenue versus projected losses.

I learned this lesson the hard way during a client pitch three years ago when I confidently presented a sales dashboard that looked fantastic on my monitor but turned into an indecipherable mess when projected on their conference room screen.

The blues blended with the greens, the reds vibrated against the purples, and my carefully researched data became completely useless.

That embarrassing moment forced me to actually understand color theory for data visualization, and honestly, it changed everything about how I present information.

Your Data Type Dictates Everything (Seriously, Stop Guessing)

Here’s what nobody tells you upfront: your data type should decide your color palette before you even think about aesthetics.

I used to pick colors based on what looked “pretty” or matched my brand colors.

Huge mistake.

Your data falls into one of three categories, and each demands a specific color approach:

Categorical palettes work for unrelated groups with no ranking or order.

Think product categories, department names, or regional divisions where no item is “more” or “less” than another.

Sequential palettes show ordered numeric progression.

Use these for quantities that increase or decrease, like sales over time, population density, or customer satisfaction scores.

Diverging palettes highlight data with a meaningful center point.

Temperature anomalies, profit versus loss, or performance above and below average all need this approach.

Getting this wrong creates instant confusion for your audience.

I once used a diverging palette (red to blue) for categorical product data, and people immediately assumed the “red” products were performing worse than the “blue” ones.

They weren’t—red just happened to be first in my random color selection.

That subtle psychological trigger completely derailed my actual findings.

Categorical Palettes: When Your Data Categories Are Apples, Oranges, and Awkward Silences

Categorical data needs distinctly different colors that your eye can immediately separate.

Here’s my hard-earned rule: stick to 6 colors maximum.

Beyond six distinct hues, your brain starts struggling to remember which color represents what, and you’re forcing your audience to constantly reference the legend.

Nobody wants to play that game during a presentation.

I keep a color swatch book on my desk specifically for testing categorical combinations before I commit them to my visualizations.

My go-to categorical combinations:

- Retro Metro: Vibrant reds, pinks, oranges, yellows, greens, blues, and purples for marketing presentations where energy matters

- River Nights: Darker reds, purples, blues, and greens for board meetings and formal reports where credibility trumps excitement

- Earthy tones: Browns, tans, olive greens, and rust oranges for environmental or sustainability data

The Retro Metro palette saved me during a product launch presentation where I needed to showcase seven different customer segments.

The vibrant, clearly distinguishable colors kept everyone engaged through 45 minutes of demographic breakdowns that could’ve been painfully boring.

For client-facing dashboards, I’ve started using printable color charts to ensure my digital choices translate properly when executives print reports.

Critical mistakes I’ve made with categorical palettes:

- Using similar hues (three shades of blue) for three unrelated categories

- Picking colors that disappeared against my background

- Choosing colors with cultural baggage I didn’t consider (like using white for a category in Asian markets where white signals mourning)

Sequential Palettes: Because Numbers Actually Have an Order (Who Knew?)

Sequential palettes fundamentally changed how I display anything with inherent progression.

Sales figures, website traffic, customer counts—anything that moves from “less” to “more” needs a gradient approach.

The concept seems obvious until you realize how many ways you can screw it up.

I originally thought sequential meant “pick two random colors and let the software blend them.”

Wrong.

Effective sequential palettes follow specific rules:

- Progress from light to dark for light backgrounds

- Move from dark to light for dark backgrounds (like presentation slides)

- Maintain consistent saturation levels throughout the gradient

- Use perceptually uniform color progression so equal data steps look like equal color steps

That last point tripped me up for months.

I created a beautiful blue gradient from sky blue to navy, but the visual “jumps” between shades didn’t match my actual data intervals.

Viewers perceived bigger changes in the middle range than at the extremes, completely distorting the story my data told.

The viridis palette solved this problem for me.

It’s specifically designed with perceptual uniformity, meaning your eye perceives equal visual differences for equal data differences.

Plus it prints well in grayscale and works for color-blind viewers, which brings me to my next point.

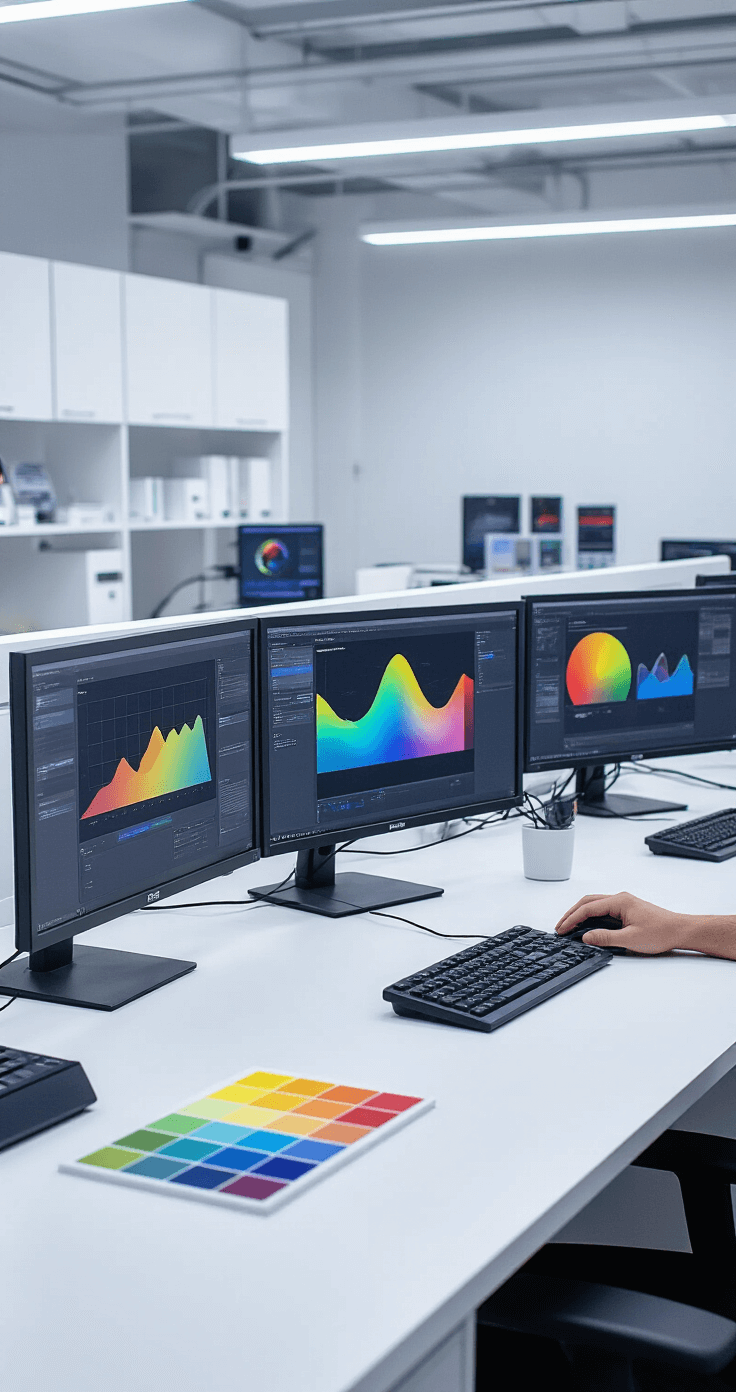

I invested in a calibrated monitor after discovering my laptop screen displayed colors completely differently than every projector I encountered.

Worth every penny for avoiding presentation disasters.

My sequential palette framework:

- Single-hue sequential: One color (like blue) progressing from light to dark for straightforward numeric progressions

- Multi-hue sequential: Two colors blending (like yellow through orange to red) for heat maps or intensity visualizations

- Reverse sequential: Dark to light for dark-themed dashboards and evening presentations

Diverging Palettes: When Zero Actually Means Something Important

I completely ignored diverging palettes until a finance director politely informed me that my profit/loss chart made gains and losses look equally “good” because I used a sequential purple gradient.

Losses and gains aren’t a progression—they’re